The Names in the Detective Hiroshi Series

The kanji for kanji. “Kanji” is usually translated as “characters” or “Chinese characters.”

One of the most challenging parts of writing a novel is naming the characters. That's doubly difficult when the names are in Japanese. And because names in Japan almost always involve kanji, Chinese characters, it's even more complicated. While these names are always written in romaji in my novels, I thought it might be interesting to explain a bit about what they mean in Japanese. Most readers of the Detective Hiroshi series are as interested in Japanese culture as they are in the mystery to be solved. Of course, culture is perhaps one of the greatest mysteries of all.

The complexity of Japanese names makes them even more fascinating. I've wanted to write about the characters' names in the Detective Hiroshi series for some time, but it's hard to explain. So, first, let me offer some Japanese language basics for those who don't know Japanese. Japanese speakers can skip down a couple of paragraphs.

Japan has two alphabets, hiragana and katakana, which function just like the alphabet in English, except they have a regular pronunciation. That should seem to simplify things, and it does, but there's also romaji, which is basically the Roman alphabet, though used slightly differently. And though some first names are written in hiragana, all family names use kanji, and 90% of first or given names use kanji, too.

Almost every kanji has multiple uses with multiple pronunciations. Each kanji character has an onyomi or kunyomi pronunciation. Onyomi is the traditional Sino-Japanese reading, which historically came from China, and often has a similar sound to Chinese pronunciation. It's usually used when two kanji go together to form a word. Kunyomi is the native Japanese reading. In Japan, meanings layer over meanings.

When I first came to Japan, I couldn't read my students' names on the first day of class. I had to ask my students to write their names in romaji on the roll sheet. Nowadays, the computer automatically provides romanization. But I still stumble over the reading of their names when handing out diplomas at graduation. The kanji are too many, too unique, and too rare. Some names are easy to read because you see them all the time, but many are very rare.

And it's not just me; many Japanese can't read the names, either. At graduation, I'll ask my Japanese colleagues, but they often have to laugh and ask the students, who also laugh. It's an amusing and beautiful burden.

The complications mount. Any form, online or paper, has a box to write the hiragana pronunciation for the kanji. Otherwise, city offices, credit cards (which use romaji), online payments, delivery notices, and everything involving people's names could be misread. That's not even including the further complication of that kanji having multiple pronunciations, some of which are never used in other situations. Some kanji have unusual pronunciations. Detective Hiroshi's given name could be rendered in many ways, with several kanji choices, each with different meanings. I didn't choose the most unusual one. I chose the one with the meaning closest to his character.

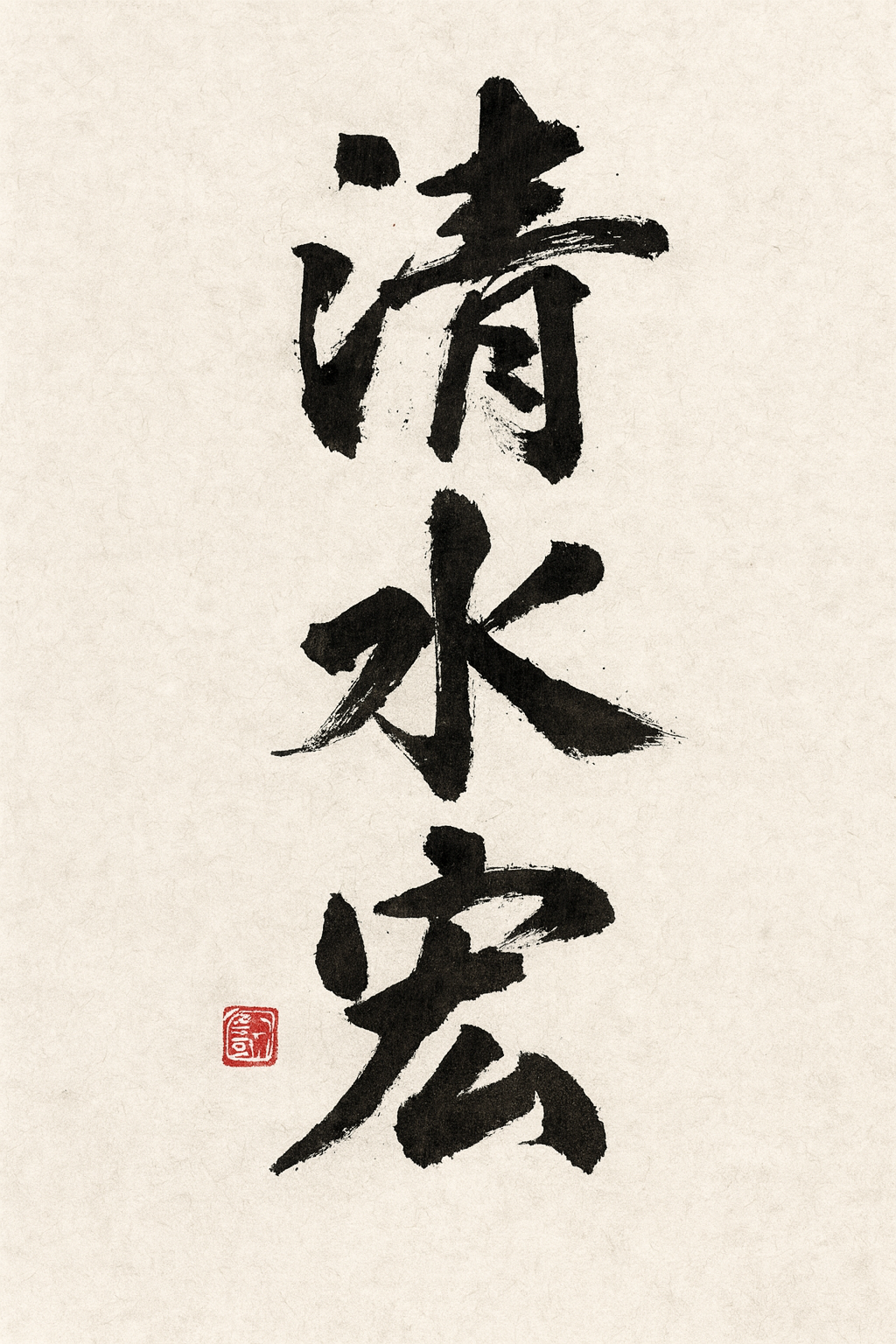

Calligraphy of Hiroshi’s name. Shimizu Hiroshi.

Let's get into the specific names. The central character in the Detective Hiroshi series is Hiroshi Shimizu, or, in Japanese order, Shimizu Hiroshi, which in kanji is 清水宏. The first two kanji, 清水, are Shimizu, three syllables and two kanji, while Hiroshi, 宏, is also three syllables but only one kanji. The family name is fortunately pronounced only one way. Both his first and last names are relatively common.

The name Hiroshi can be written with a variety of kanji. 博, 博史, 広志, 博志, 浩士 are all possibilities. Some are one kanji, and some are two kanji. You can see why I'd stumble over reading the roll in class. I chose 宏 as the character's name for several reasons.

First, I was thinking of the pronunciation. There are so many beautiful names in Japanese, but many of them are hard to pronounce, even when written in romaji in an English-language novel. Hiroshi is relatively easy for English speakers to get their tongues around, and so it's easier to remember.

Then, like any parent naming a child, I have hopes for the character. Hiroshi 宏 means broad, large, great, or expansive. That fits him in his work as a detective, where he is more interested in the big picture than the often-grim details. He thinks big, not small, and has a big heart and broad perspective. That name fits his character.

In a larger symbolic sense, his family name fits his character as well. His family name, Shimizu, written 清水, means clear (or pure or clean) water. Water plays an essential role in Buddhism, with significant symbolic import. Water imagery, as well as actual water, is commonly part of the practice of most religions. I don't think Detective Hiroshi is a religious type, but if you notice when his last name crops up in the novels, you can see moments when clear water is needed.

I break Japanese convention in the novels, though, by referring to him by his given name. The Japanese use family names, usually with san added unless they are close or intimate. I call my students by their given names, but my Japanese colleagues call them by their family names. I want students to feel comfortable with the foreign practice of using first or given names as they prepare for their future work at global companies.

I use "Hiroshi" to give readers a sense of closeness to the character and to give him a tinge of Western, global feeling, which he picked up studying in Boston. It makes it easier for non-Japanese readers to connect with him.

I also don't use Hiroshi's name attached to the title of his position as a detective. The office staff at my university would call me "sensei" or use "Pronko sensei" if another sensei were in the room. In one-on-one emails, many colleagues use my first name, Michael. But if there is a group email, they'll use "Pronko sensei" to maintain respect. Likewise, in Japanese, Hiroshi would most likely be called "Detective" because he's doing his job. At most, it might be "Detective Shimizu" as a referent to distinguish him from the other detectives in the room or in the discussion.

But since that would distance English-language readers, and even more importantly, put the emphasis on his actions as a detective and not as a human, I kept it as Hiroshi. I wanted the focus to be on his personal reactions more than his social actions. Hiroshi keeps the subjective point of view. "Detective" sounded too formal, and therefore too distant. That's appropriate in social contexts in Japan, but reading a novel is a more intimate undertaking.

The only other possibility for Hiroshi's name in kanji would be 博, but that's a kanji that is used for PhD doctoral status. That fits in a way, since he has a degree and is respected, but it would accent the logical procedures and higher learning rather than his gut reactions and conscience. Hiroshi is highly educated but also highly intuitive.

OK, so that's one character's name.

Takamatsu, the chain-smoking old-school detective who doesn't mind bending a few rules to get a good result, has a rather traditional-sounding name. It's his family name, which is also not uncommon. 高松 means very simply "tall pine." That fits him, considering how long he's lived while smoking so many cigarettes. The two kanji are common ones. 高 "taka" means tall, a common word used in many contexts. Takamatsu himself is not tall in the novels, but he's symbolically tall as the senior detective with the most experience, both good and bad. 松 "matsu" means pine tree.

Pine trees are considered a symbol of longevity, courage, and endurance. You see branches in front of homes and companies at the new year, in traditional paintings, and in Japanese gardens. In my backyard, I have a pine tree, which I keep trimmed so it doesn't get too tall. I look out at it when I'm writing for a bit of encouragement, though the scenes with Detective Takamatsu in them are usually the most fun to write.

Detective Sakaguchi's name is fairly simple, too, with a hint of irony. Sakaguchi, 坂口, has two characters: the first, "saka," meaning "slope," and the second, "guchi" (also pronounced "kuchi" or "ko"), meaning "mouth," "entry," or "opening." It is a very common family name, and, like many Japanese names, perhaps originally referred to the place where a family might have lived. It's a common name in western Japan, too, which fits since Sakaguchi is from Osaka. The sense of sloping here is more like that in a city, where a steep slope is hard to climb. As an ex-sumo wrestler, Sakaguchi is heavy and tall. Looking up at him would be like looking up a slope or a steep set of stairs. And yet, he has an openness that helps crack the cases. The two kanji are easy to write and read.

Ayana, Hiroshi's girlfriend who works as an archive librarian at the National Archives, has an appropriately lovely name. 綾奈 has, again, two kanji. The first kanji is often used for silk fabric with patterns. It's a complex kanji with many strokes. I can't write it from memory, and I guess many Japanese can't either. I can write the left radical in the first kanji, since it's common, but I'd fumble the right side. And that's not even to the second kanji. Her name's kanji has 14 strokes, which is above average. That compares to 3 strokes for Sakaguchi's second kanji.

The second character in Ayana's name used to be fruit, and is often used in women's names. Yes, names are highly gendered, but that's changing. Some might point out the gender roles entrapped in the naming of women in Japan. That's true to some extent, since women's names are often associated with fertility, beauty, and other traditional roles, or used to be. Now, they are more empowering, but still poetic. On the first day of my poetry class at a women's university where I teach part-time, I have the students write their names in kanji on the blackboard. The twenty-some names on the board, in students' own handwriting, form a marvelous, impromptu poem that also stuns me. I tell them their names are poems.

Hiroshi's assistant, without whom he could not function, is named Akiko. This is a very common name, or used to be. These days, parents tend to drop the "ko" 子kanji, which also means "child." That does feel sexist, and many women simply drop the "ko" with friends or classmates. Though there are many, many ways to write Akiko, in the novel, I always think of Akiko's name in kanji as 亜希子. Those three kanji mean (in order) Asia or sub, hope, person (or child). That fits Akiko since she's brilliant at searching online, organizing evidence, finding information, and channeling crucial office gossip.

The three other detectives in the first several novels are Osaki 大崎 (large, tip), Sugamo 巣鴨 (nest, duck), and Ueno 上野 (upper part, field). However, I selected these names as a sort of inside joke. While all three names are common family names, they are also the names of three stations along the Yamanote Line, which circles central Tokyo. On any train ride on the Yamanote, you'd see those names pop up on the map. The areas around those stations would also be referred to as Ueno or Sugamo.

Here’s the name I used in China, Mike

Ono, the private detective called in for outside-the-box help, has a name with two possibilities. It can be read as Ono 小野, with a single "o" sound, or Oono 大野, with a long "o" sound. He's short and squat, so one fits, but round, so the other fits. Ono's boss at the private detective agency is Shibutani, an old ex-detective friend of Takamatsu's. He hires Takamatsu after Takamatsu was forced to retire(though still active as a PI). His name, Shibutani 渋谷, translates as "bitter (or rough) valley." Of course, the degree to which names still carry the meanings from the kanji is open to discussion. Most Japanese probably think of it as just a name, without going into the analysis too much.

Of the newest regulars, three new detectives joined the department to manage the task force on crimes against women. Unfortunately, they're often dragged away to help with any homicide when needed, and women get the short end of the stick again. Their names were carefully chosen for both pronunciation and meaning. First is Ishii 石井, whose name uses the kanji for stone and for well (a well with water). It's easy to guess the origin of such a name, but in terms of the symbolic meanings of the novel, her strength and depth are neatly captured in her name.

Working with Ishii is Adachi 足立, a specialist in shooting, one who's won numerous pistol and rifle awards. The two kanji in her name are pretty commonly used for family names and for one of the wards in Tokyo. The first kanji means 'foot,' and the second means' stand' or 'establish,' so the name conveys a sense of being grounded and stable. She's a solid, reliable, and resilient member of the force.

The newest member is Kim 金. She's Korean but grew up in Japan, so she speaks Japanese fluently, as well as English. Her single-character family name means gold, metal, or iron, and is also used for money, or anything related to money. Names also serve as foreshadowing. In this case, she's not wealthy in material terms; she's wealthy in strength and grit, as emphasized by her high level of Taekwondo, the Korean martial art that primarily uses kicking, punching, and blocking.

I've already rambled on here too long, and I haven't even gotten to the villains, whose names are perhaps more clearly loaded with more certain meanings. I'll handle the names of villains in the novels in the next installment.

My name in Japanese katakana, Michael Pronko